Now, a team of researchers from the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, UCLA's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Israel's Tel Aviv University has developed an innovative approach to the study of genetic diversity called spatial ancestry analysis (SPA), which allows for the modeling of genetic variation in two- or three-dimensional space.

Their study is published online this week in the journal Nature Genetics.

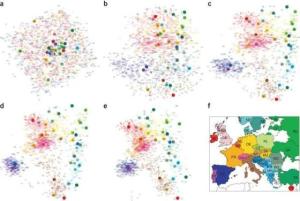

With SPA, researchers can model the spatial distribution of each genetic variant by assigning a genetic variant's frequency as a continuous function in geographic space. By doing this, they show that the explicit modeling of the genetic variant frequency -- the proportion of individuals who carry a specific variant -- allows individuals to be localized on a world map on the basis of their genetic information alone.

"If we know from where each individual in our study originated, what we observe is that some variation is more common in one part of the world and less common in another part of the world," said Eleazar Eskin, an associate professor of computer science at UCLA Engineering. "How common these variants are in a specific location changes gradually as the location changes.

"In this study, we think of the frequency of variation as being defined by a specific location. This gives us a different way to think about populations, which are usually thought of as being discrete. Instead, we think about the variant frequencies changing in different locations. If you think about a person's ancestry, it is no longer about being from a specific population -- but instead, each person's ancestry is defined by the location they're from. Now ancestry is a continuum."

The team reports the development of a simple probabilistic model for the spatial structure of genetic variation, with which they model how the frequency of each genetic variant changes as a function of the location of the individual in geographic space (where the gene frequency is actually a function of the x and y coordinates of an individual on a map).

"If the location of an individual is unknown, our model can actually infer geographic origins for each individual using only their genetic data with surprising accuracy," said Wen-Yun Yang, a UCLA computer science graduate student.

"The model makes it possible to infer the geographic ancestry of an individual's parents, even if those parents differ in ancestry. Existing approaches falter when it comes to this task," said UCLA's John Novembre, an assistant professor in the department of ecology and evolution.

SPA is also able to model genetic variation on a globe.

"We are able to also show how to predict the spatial structure of worldwide populations," said Eskin, who also holds a joint appointment in the department of human genetics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. "In just taking genetic information from populations from all over the world, we're able to reconstruct the topology of the global populations only from their genetic information."

Using the framework, SPA can also identify loci showing extreme patterns of spatial differentiation.

"These dramatic changes in the frequency of the variants potentially could be due to natural selection," Eskin said. "It could be that something in the environment is different in different locations. Let's say a mutation arose that has some advantageous property in a certain environment. So you can imagine then that a kind of force for genetic selection would make this mutation more common in that environment."

The research team began to examine all of the genes, and for each gene they computed how sharp of a change there was in the frequencies. They soon discovered that the genes which had the largest and most extreme changes are the ones that are known to have experienced selection in the recent past.

"So this is a new method for finding genes that are also undergoing selection in humans," Yang said.

www.sciencedaily.com

English

English Vietnamese

Vietnamese